The pioneering building that scandalised Paris

The daring, radical Pompidou Centre was derided by many when its design was first unveiled – yet it has continued to influence the architecture of public buildings ever since. As the building approaches a major renovation, its co-creator Renzo Piano recalls the furore.

This summer, the Centre Pompidou will close for five years, as Paris's popular polychrome landmark undergoes changes necessitated by current requirements in terms of health, safety and energy efficiency. French studio Moreau Kusunoki Architects, Mexican practice Frida Escobedo Studio and French engineer AIA Life Designers will undertake a major overhaul of the six-storey arts centre, containing Europe's largest museum of modern art. Its renovation will add usable floor space, remove asbestos from all facades, improve fire safety and accessibility for people with reduced mobility, and optimise energy efficiency.

As far as possible, the original building will be conserved as it was before. To do otherwise might be considered cultural sacrilege – after all the Pompidou's identity is indivisible from its original architects, Renzo Piano, and the late Richard Rogers. The duo set up their practice, Rogers + Piano, in 1970, and submitted a design to a prestigious competition instigated in 1971 by Georges Pompidou, France’s President from 1969 until 1974. Its jury was headed up by Jean Prouvé, a metalworker and self-taught architect, and included such stellar architects as Philip Johnson and Oscar Niemeyer. Piano and Rogers' design was chosen from 681 competition entries.

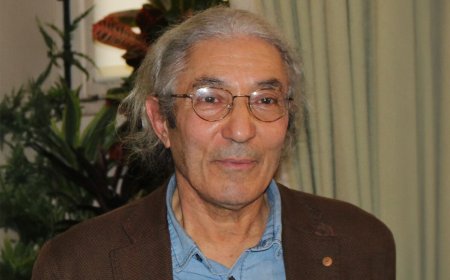

The result caught the duo, then unknowns in their 30s "with Beatles haircuts", as Piano puts it, by surprise: "We didn't think we'd win, we entered the competition for pleasure," the Italian architect, now 87, tells the BBC. "We never planned to create a revolutionary building. Our idea was a museum that would inspire curiosity, not intimidate people, and that would open up culture to all."

In fact, the duo's insouciance may help to explain the building's uninhibited boldness, flamboyance and ludic quality. Its structural elements and services were placed on its facades, allowing it to maximise its internal, open-plan spaces – and prompting the futuristic structure to be dubbed the world’s first "inside-out" building. Its exoskeleton of tubes and periscope-like pipes were playfully colour-coded: blue for air-conditioning, yellow for electricity, green for water and red for pedestrian circulation. Visitors streamed up escalators – encased in transparent tubing affording panoramic views – that were designed to reinforce the museum's connection to the city.

"Our idea was for the building to take up only half the site, allowing for a welcoming outdoor place – a piazza – where people could meet," says Piano, whose other projects include the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco (rebuilt in 2008), the Shard (2012) in London, and the recently completed Paddington Square, also in the UK capital, a mixed-use building and public square. "Our credo was a place for all people – for the poor and rich, the young and old."

The Pompidou's transparency, accessibility and adjacent piazza chimed with new ideas about democratising culture. "Street theatre and concerts in public spaces were rising in popularity at the time," says Piano.

Inside the building, visitors had access to the Bibliothèque Publique d'Information – Paris's first free public library – the Musée National d'Art Moderne and the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/ Musique (IRCAM), dedicated to research of music and sound.

Piano and Rogers' winning entry provoked consternation and fury when it was announced at a press conference: "The room was packed," remembers Piano. "Richard and I were standing in the middle of the room being heckled. We felt elated yet terrible at the same time," says the architect. "Some people were shouting, 'Why have you designed something so horrible?' 'Why are you are destroying Paris's historic centre?'"

Although surprised to have won the contest, Genoa-born Piano grew up feeling architecture was his destiny – aged 18, he told his father he wanted to be an architect. However in conversation his manner is humble, not entitled. Born into a family of builders in Genoa, he loved watching his father's work take shape. Perhaps his childhood experience of seeing buildings materialise successfully made him feel that architecture is open to all possibilities. "Building is a beautiful gesture," he once told The Financial Times. "It's the opposite of destruction… especially when you are creating buildings for people because they are civically important." In 1981, Piano founded the Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW), with offices in Genoa and Paris, led today by 11 partners (in the spirit of a collective). In 1998, he won the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

(Source:BBC)