Literary Memory and Cultural Resistance: Documenting the Yazidi Genocide

By: Sirwan Abdulkarim Ali / PhD in English Literature and Cultural Studies from the University of Western Australia

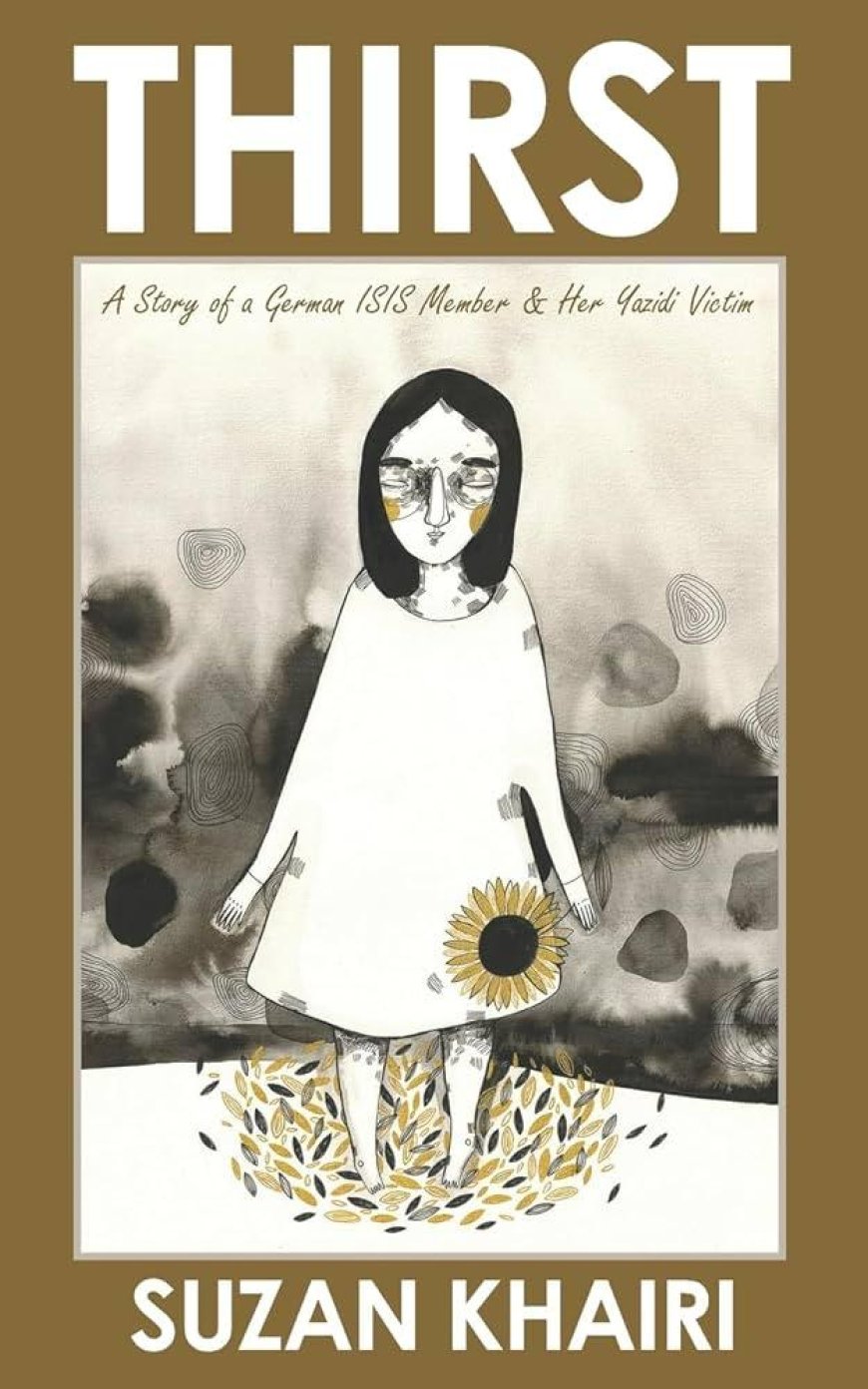

The Yazidi genocide of August 2014, perpetrated by ISIS, stands as one of the most brutal atrocities of the 21st century. The massacre, forced displacement, and systematic sexual enslavement of Yazidi women left deep psychological, cultural, and historical scars. In the face of such trauma, literature emerges not only as a space for mourning and testimony but also as a site of cultural resistance and renewal. Suzan Khairi’s Thirst is among the first literary works to document this genocide from an insider’s perspective, providing readers with a powerful narrative of survival, suffering, and the unbroken spirit of the Yazidi people.

Khairi’s Thirst is the story of a German ISIS member who is deeply rooted in the experiences of Yazidi women, particularly those subjected to sexual violence. Her work is important because it gives voice to those historically silenced. For the first time in the modern history of the Middle East, women who endured sexual violence have begun to speak and write publicly about their trauma—an act of radical defiance and cultural courage. This phenomenon echoes post-WWII Germany, when German women who had suffered sexual violence during the Soviet invasion began to tell their stories, defying the stigma and collective silence.

In Thirst, Khairi constructs her characters with emotional complexity and dignity. These women are not merely victims; they are survivors, bearers of memory, and agents of resilience. Her protagonist embodies the Yazidi struggle for survival, often flactuating between despair and resolve. She is shaped not only by her trauma but also by the cultural richness of Yazidi identity—her connection to land, myth, and spiritual heritage. This careful construction allows readers to understand the genocide not only as a moment of destruction but also as a rupture in a long-continuing cultural lineage.

That said, while Khairi’s contribution is invaluable, there is significant room to support her artistic growth. Literary quality matters deeply in ensuring these stories are not only recorded but also absorbed and remembered widely. Khairi’s style would benefit from structural refinement, deeper psychological introspection, and stronger narrative cohesion. Supporting Yazidi writers through mentorships, translation opportunities, and publication networks can help elevate such works to international platforms, ensuring the genocide is not forgotten and that Yazidi voices remain central in global cultural memory.

More literary efforts like Thirst are needed—not just for documentation but also for healing. Writing can be a form of therapy for communities recovering from collective trauma. In narrating their pain, Yazidi writers affirm the existence and resilience of their people. By preserving memory in literature, they resist erasure and create space for cultural regeneration. The courage of the Yazidi women who have spoken out defies centuries of patriarchal silencing in the region, offering a powerful cultural shift that demands scholarly attention.

Finally, Suzan Khairi’s Thirst marks a crucial step in Yazidi cultural preservation and resistance. Documenting the genocide through literature allows for global recognition of their suffering and highlights the strength of Yazidi women as cultural narrators and survivors. As a cultural scholar, investing in this field of study not only honors their voices but also contributes to broader discussions on trauma, memory, gender, and resilience in post-conflict societies. The future of Yazidi literature lies in supporting such voices, refining their tools of expression, and ensuring that hope, rather than horror, becomes the final word.